Lacrosse's Struggles and the Rise of Boxla

Decade: 1920s-1930s

Theme: Lacrosse's struggles and the rise of boxla

Despite the innovations of the interwar years - and the introduction of a new form of lacrosse that became dominant among the province's players - the 1920s and 1930s represented an era of decline for Manitoba lacrosse. This might have been the result of rough play - which alarmed lacrosse's amateur leaders and put off potential spectators - or competition from the growing number of alternative commercial sports and spectacles during this period. Or perhaps, as journalist Vince Leah noted, "when the game was dropped from the schools' sports program minor lacrosse withered along with it."[1] Regardless, by the late-1920s lacrosse in Manitoba was suffering from a general lack of interest as the number of teams playing in local leagues began to dwindle.

The two decades between World Wars were characterized initially by the resurgence of amateur sport. Prominent amateur sport leaders touted the benefits of participation to a nation looking to heal from the devastation and deprivation of the First World War and the subsequent influenza outbreak of 1919. The prominence of elite events such as the Olympics, to which lacrosse would return as a demonstration event in 1928 and 1932, were intended to highlight the rewards of a dedication to amateur values. The increasingly prominent newspaper sports pages, along with newsreels played in movie houses and the new and wildly popular radio sets, brought the success of athletes into people's homes making heroes of sportspeople from far off places. But, as the post-war boom gave way to the Great Depression, amateur sport suffered and commercial spectacles grew in prominence. Entrepreneurs like Conn Smythe in Toronto built spectator-focused facilities such as Maple Leaf Gardens that would house a wide variety of events, including the newest form of lacrosse.

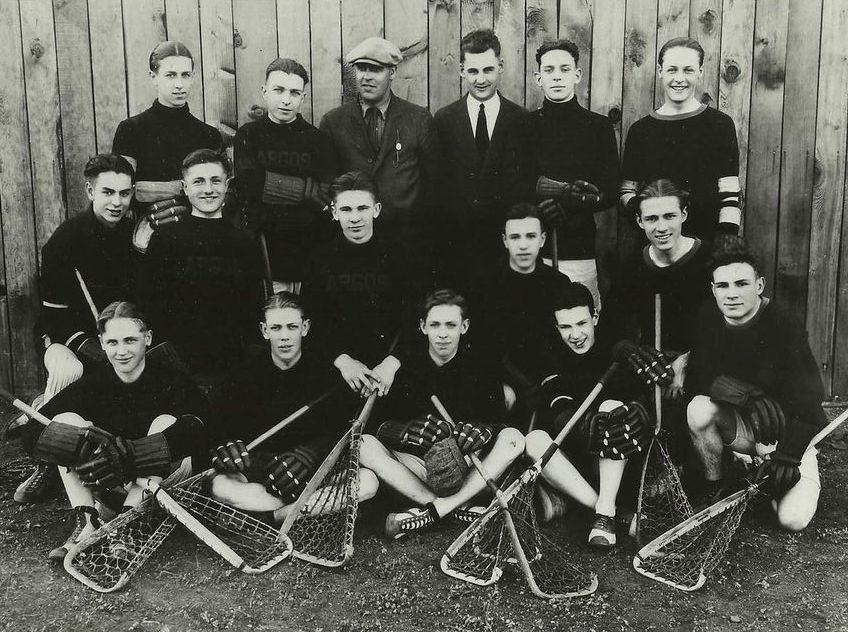

The shifting fortunes of amateur lacrosse in Manitoba in this period were exemplified in Winnipeg during the middle years of the 1920s. The playoffs for the city's senior championship in 1923 ended in ignominy when the semi-final playoff series between the Nationals and Fort Rouge, who were playing for the right to meet the Tammany Tigers in the championship series, was cancelled after a game was abandoned when players began fighting and officials could not restore order. The stick-swinging incident led the Winnipeg Amateur Lacrosse Association (WALA) to first cancel the remainder of the playoffs, leaving the season without a champion, and then recommend to national amateur sport officials that five Nationals players be banned for life. Lacrosse resumed the following year with the Argonauts replacing the Nationals in a three-team senior division, but while there were four teams in the midget division, there were only two juvenile teams and no junior teams competing in the city in 1924. Despite this seeming lack of interest in the sport, Winnipeg hosted the national meeting of the Canadian Lacrosse Association in 1925 and Abbie Coo, a Winnipeg Free Press reporter, the newspaper's eventual editor, and also a member of the WALA, was elected the national association's president.

Within these conditions, local lacrosse administrators undertook a number of schemes to improve the sport's popularity. A special tournament was organized in 1919 to coincide with the arrival of the Prince of Wales in Winnipeg, while in 1923 the Montreal Shamrocks were invited to Winnipeg to contest a three-team tournament against the Tammany Tigers and Fort Rouge, won by the visitors. In 1921, the WALA, created what it called a Permanent Lacrosse Council to investigate ways to make the game more popular. Council projects included debating rule changes to make lacrosse more appealing, working with the Winnipeg School Board to promote their lacrosse league, fundraising efforts to build increased seating capacity at local grounds, and hosting games at high-profile civic festivals. Local press blamed the Council for the events that led to the city's 1923 senior playoffs being abandoned and it ceased to exist after its three-year mandate ended.

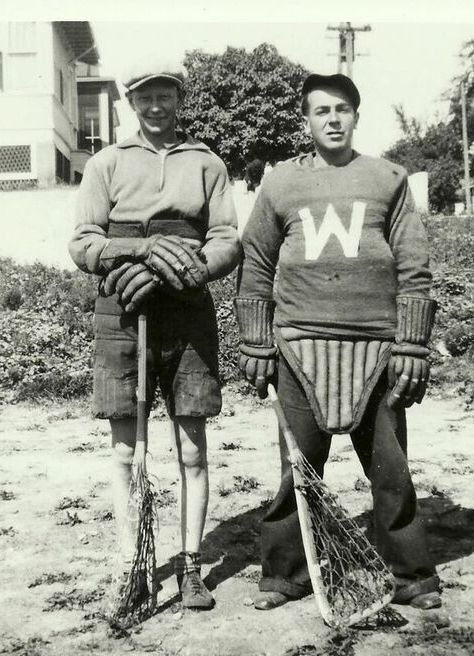

Despite the setbacks of this period, there were moments of success as a handful of clubs continued to thrive. Winnipeg teams reached the finals of the Mann Cup competition three times during this era, after the competition shifted from a challenge format to a playoff series, including two attempts by the Tammany Tigers at winning the national senior championship. This club, which fielded teams in a number of sports, was one of the highest-profile of the Winnipeg-based teams in this era. The Argonaut lacrosse club of Winnipeg - coached by Hockey Hall of Fame inductee, Frank Fredrickson - also reached the Mann Cup finals in 1932. When the organizers of the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles decided to include field lacrosse as a demonstration event, the team named by the Canadian Amateur Lacrosse Association consisted primarily of players from the hotbeds of Ontario and BC, but also included two Manitoba players: Hall of Fame inductees Dick Buckingham (defenseman) and Frank Hawkins (goaltender).

Provincial lacrosse had become a largely Winnipeg-based sport by this period. One exception was the western Manitoba village of Rapid City, with a population of less than 500, whose team in 1932 challenged (unsuccessfully) for the senior provincial championship. Lacrosse was played throughout the capital city, including at Sherburn Park on Portage Ave. West and Main Street Stadium on South Main Street. But these were primarily multi-sport facilities and lacrosse teams had to share grounds with baseball teams (a more popular sport in this era) and other pastimes. Local teams that regularly used the grounds of Wesley Park, Manitoba College, also faced scheduling conflicts with other sports and events. Throughout this period finding playing fields was a challenge for many teams.

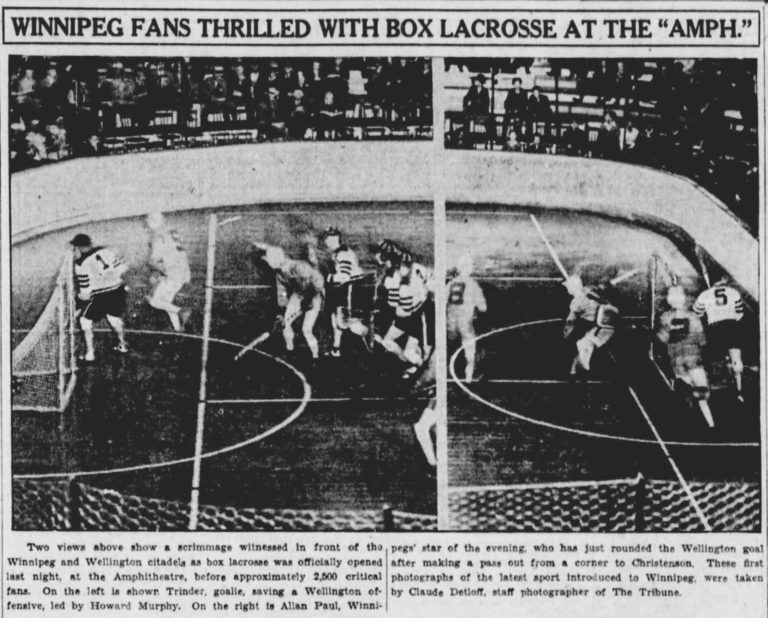

One venue that did begin to host lacrosse games in this period was the new Winnipeg Civic Auditorium, which opened in October 1932. While it did not include an ice plant for hockey, the Auditorium offered the city a modern new arena in which to house a variety of events. With the dwindling popularity of field lacrosse in an era of prominent commercial spectacles during the Great Depression - from professional hockey at new arenas such as the Montreal Forum and Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens to the rise of movie houses and talking motion pictures - a new form of lacrosse emerged to take advantage of these trends. Sports entrepreneurs, led by Joe Cattaranich and Leo Dandurand of the Montreal Canadiens, sought a way to fill dates in their hockey arenas during the quieter summer months. One initiative was the creation of an indoor version of lacrosse, known as box lacrosse (or "boxla"). Played six-a-side on the cement floors of hockey rinks, with the boards creating smaller field dimensions, the game was fast - and soon came to be promoted as "the fastest game on two feet" (a moniker coined by Vancouver sports broadcaster and Winnipeg native, Leo Nicholson). One impact of the introduction of box lacrosse was that the field version of the game virtually disappeared in the 1930s. In Canada, as Donald Fisher notes, the "abandonment of field lacrosse in favor of the box version of the game was quick and complete."[2]

In 1932, Manitoba responded to pressure from the rest of the Canadian lacrosse community and embraced box lacrosse. The WALA changed its name to the Winnipeg Indoor Lacrosse Association. Manitoba teams competed nationally in boxla, but the game had found its strongest footholds in BC and southern Ontario. The Wellingtons travelled to the west coast in 1934 to play the New Westminster Salmonbellies in the Western Canada playoffs to would determine which team would face the Ontario champion for the Mann Cup. While the Winnipeg club held its own in losing 12-8 in the first game of the best-of-three series, the 33-5 loss in game two was a bellwether of Manitoba's fortunes nationally. Although the Wellingtons would return to BC in 1939 - this time losing to the New Westminster Adanacs - box lacrosse was suffering in Manitoba. With fans and players reluctant to spend their summer nights inside watching lacrosse, participation, attendance, and coverage in Manitoba dipped to low levels. But that would soon change as the new indoor game morphed further and, especially in one Winnipeg neighbourhood, moved outdoors.

Significant achievements

1918: failed challenge for Mann Cup (Winnipeg Lacrosse Club)

1919: failed challenge for Mann Cup (Argonauts)

1926: Mann Cup finalist (Tammany Tigers)

1928: Mann Cup finalist (Tammany Tigers)

1932: Mann Cup finalist (Argonauts)

1932: Olympic demonstration sport

Winnipeg city champions (partial)

| Year | Senior | Junior | Juvenile | Midget |

| 1920 | Fort Rouge (Wpg) | |||

| 1921 | Nationals | St. John's | Argonauts | |

| 1922 | Tammany Tigers | Elmwood Pirates | Argonauts | |

| 1923 | [playoffs cancelled] | Tammany Tigers (?) | ||

| 1924 | Tammany Tigers | [no competition] | Argonauts | Argonauts |

| 1925 | Tammany Tigers | |||

| 1926 | Tammany Tigers (?) | |||

| 1927 | Argonauts | |||

| 1928 | Tammany Tigers (?) | Wellingtons | ||

| 1929 | ||||

| 1930 | ||||

| 1931 | Maroon Athletic Club | |||

| 1932 | Argonauts (?) | |||

| 1933 | ||||

| 1934 | Wellingtons (?) | |||

| 1935 | ||||

| 1936 | ||||

| 1937 | ||||

| 1938 | ||||

| 1939 | Wellingtons (?) |

Learning lacrosse

Field lacrosse vs. box lacrosse

The sport of lacrosse began as an outdoor sport, with the original codification by George Beers setting out a 12-player game. Today the game is played with 10 players a side. Box lacrosse, or "boxla," the modified and indoor version of the game rose to popularity in the 1930s. Entrepreneurs in eastern Canada looking to fill dates in their new arenas created a six-on-six, indoor version of lacrosse. In Manitoba - Winnipeg in particular - boxla took off as an alternative to field lacrosse, but was often played outdoors within the boards of hockey rinks when ice was not installed.

Hall of Fame inductees

Richard Henry (Dick) Buckingham

References

[1] Vince Leah, Pages from the Past (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Tribune, 1975), p. 161.

[2] Donald M. Fisher, Lacrosse: A History of the Game (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), p. 157.

[3] Fisher, Lacrosse: A History of the Game, p. 164.